“Does anyone have any antibiotics I can borrow? My husband is sick and has an important presentation for work, but the doctor here won't prescribe them.” “My child has a sore throat with fever. I'm sure it's strep throat, but the doctor is making us wait! Does anyone have any amoxicillin they don't need?”

These are some of the many calls for help in an online expat group, where members rely on each other for the types of help they are accustomed to in their home countries. The use of antibiotics and quick fixes has become customary for many of us, especially those who’ve come of age in an era of fast service and instant gratification. Unfortunately, the modern miracle of antibiotics has suffered from easy availability and overuse, resulting in one of the world’s most pressing health issues: antibiotic resistance. Tackling this resistance is a high priority for the World Health Organization (WHO), which endorsed a global plan for action at the World Health Assembly in 2015, requesting all countries to develop national action plans by 2017. This was followed by a political declaration by heads of state in 2016, committing to addressing the causes of antimicrobial resistance across all sectors and supporting the development and implementation of activities at the national, regional and global levels.

Antibiotics in primitive forms have been used to treat infections for thousands of years: in ancient Egypt, for instance, moldy bread was used to treat infected wounds, although the causal role of bacteria in infections was not understood until early in the twentieth century. Around the world at that time, scientists were beginning to make discoveries related to bacteria and infections and how to treat them. In 1928, by a combination of accident and shrewd observation, Alexander Fleming discovered that a fungus, Penicillium notatum, was able to kill Staphylococcus bacteria. This led to the eventual mass production of penicillin, the antibiotic chemical produced by this fungus. Penicillin was widely used to treat wounds during World War II and all manner of infections in the general population, and was considered a true miracle of modern medicine. The discovery of other antibiotics (produced by soil bacteria) – such as streptomycin, tetracycline and chloramphenicol – followed, heralding what is known as the “antibiotic age.”

Since then, many antibiotics have been developed and used successfully for the prevention or treatment of bacterial infection in cases such as burns, surgeries, wounds, respiratory tract infections, sexually transmitted diseases, urinary tract infections, diarrhea and countless other applications. But... microbes are smart, and driven by evolution, they have adapted to survive attacks not only by other microbes but also by antibiotics. This ability of bacteria to change and withstand the effects of antibiotic drugs is known as antibiotic resistance, viewed by the WHO as one of the largest threats to global health and food security today.

Although antibiotic resistance is a natural occurrence, this phenomenon is stimulated and accelerated by mis- and overuse of antibiotics in humans, animals and agriculture. To combat these practices, the WHO's global action plan on antimicrobial resistance has five objectives:

- to improve awareness and understanding of antimicrobial resistance

- to strengthen knowledge through surveillance and research

- to reduce the incidence of infection

- to optimize the use of antimicrobial agents

- to develop the economic case for sustainable investment that takes account of the needs of all countries, and increase investment in new medicines, diagnostic tools, vaccines and other interventions.

Although it is illegal in the US and many other countries to buy antibiotics without a prescription, they are easily purchased on the internet either without a prescription or using an online prescription provided by the seller, a practice which permits self-medication and limits the quality of care. Globally, many countries sell antibiotics without a prescription, resulting in inappropriate and ineffective treatment, overuse and antibiotic resistance. In developing countries, many times the only medical help available is a local pharmacy, which dispenses antibiotics without full knowledge of the best treatment, increasing the chance of antibiotic resistance. The WHO's global action plan addresses these realities so that changes can be made.

Another area contributing to antibiotic resistance is farming. In the US alone, 80% of antibiotics sold are used on livestock. Antibiotics are also commonly used on crops and in aquaculture, particularly in countries where clean water for use in aquaculture is limited. Reported among the greatest users of antibiotics in aquaculture are China, Vietnam and Bangladesh. Intensive farming practices utilize antibiotics both as growth promotors and prophylactically. Before January 2017, large amounts of antibiotics were available for sale without prescription in any farm store in the US. After that date, new regulations by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required a prescription from a veterinarian and banned the use of antibiotics to make animals fatter. Since then, tests of meat from livestock slaughtered in the US have unfortunately shown that levels of antibiotics are still high, indicating that more action needs to be taken.

As incidences of antibiotic resistance have increased globally, the numbers of deaths from infections have also increased. In the US alone, 23,000 deaths yearly are attributed to this. Globally, it has been estimated that 700,000 deaths per year occur as a result of antibiotic resistance. There have even been reports of resistance to the antibiotic Colistin, which has been used once again as a last resort, after falling out of favor due to its serious side effects such as kidney toxicity, indicating the seriousness of the situation.

As incidences of antibiotic resistance have increased globally, the numbers of deaths from infections have also increased. In the US alone, 23,000 deaths yearly are attributed to this. Globally, it has been estimated that 700,000 deaths per year occur as a result of antibiotic resistance. There have even been reports of resistance to the antibiotic Colistin, which has been used once again as a last resort, after falling out of favor due to its serious side effects such as kidney toxicity, indicating the seriousness of the situation.

The discovery of antibiotics changed the world. Diseases such as pneumonia, tuberculosis and common infections, which once were killers, became treatable and curable. But mis- and overuse of antibiotics has placed us in the precarious position of a possible post-antibiotic world. Without antibiotics, many more deaths will occur in burn victims, cancer patients, premature babies and AIDS patients, among others. Organ transplants and surgeries will become impossible. Dialysis and childbirth more risky. Without antibiotics for treatment, common infections will once again become life-threatening. This is why the WHO considers antibiotic resistance one of the largest threats to global health and food security today.

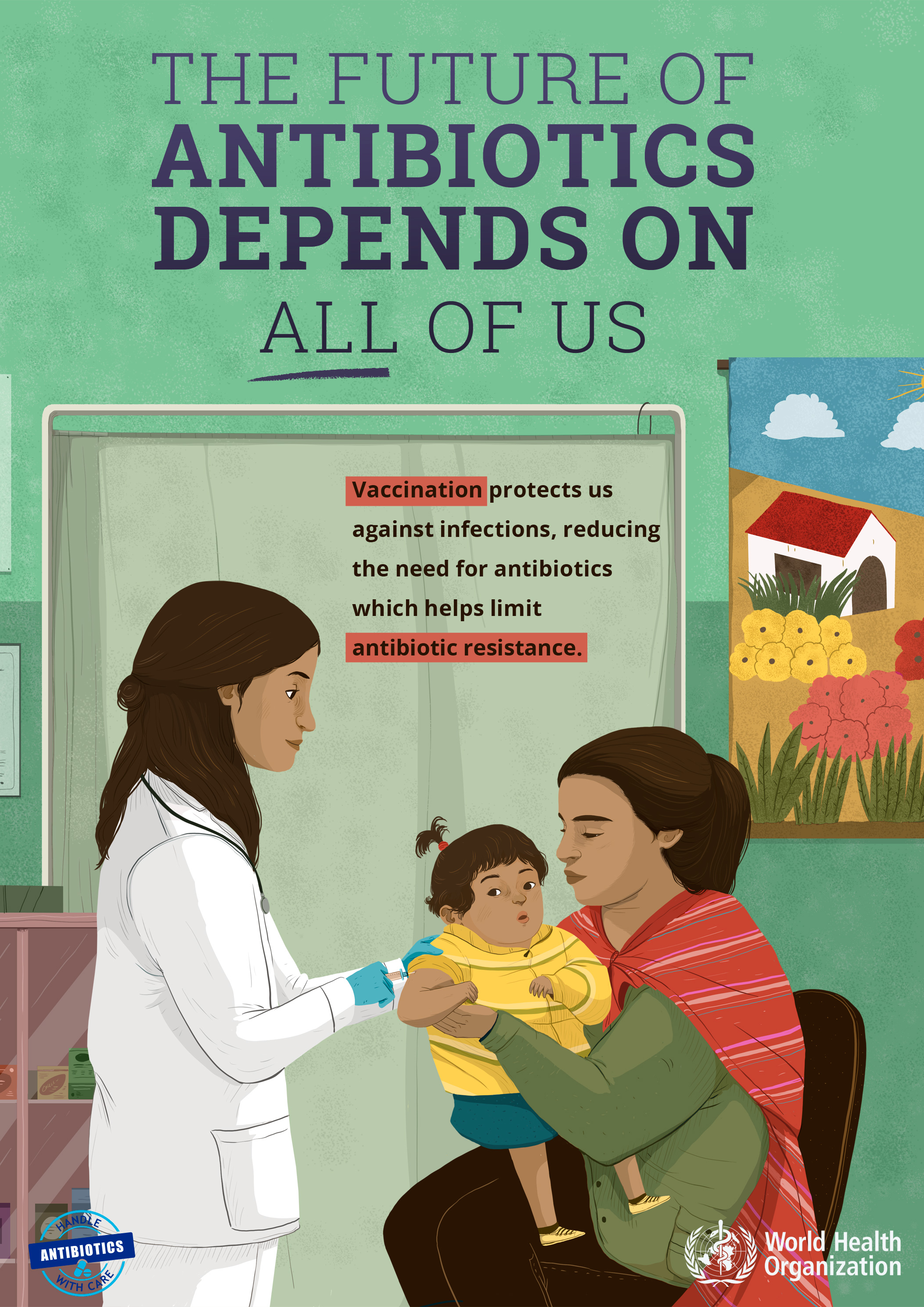

What can be done? An emphasis on immunization, infection prevention, hygiene, safe water and sanitation is vital. Education for professionals and policy-makers is necessary, so that the dispensing of unnecessary and inappropriate medications is curtailed. Changes within the pharmaceutical industry, such as sales practices (eliminate commissions for volume of drugs sold) and investment in research and development to develop new medicines and rapid diagnostic tests. Increase a sense of personal accountability, so that people do not pressure their doctor to give them antibiotics for frivolous or inappropriate use. If prescribed antibiotics, follow the usage instructions exactly. Do not use leftover antibiotics or share them with others. Understand that antibiotics will not cure viral infections such as colds, flu, bronchitis, and some ear and sinus infections, and taking them for those illnesses is inappropriate and irresponsible. In 2019, the WHO observes World Antibiotic Awareness Week from November 18–24 to increase awareness of resistance and encourage best practices to limit its spread. We can all do our part!

Sources:

https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance

https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/antibiotics/art-20045720

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(16)30093-6/fulltext

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2731226/

https://cddep.org/research-area/antibiotic-resistance/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4486712/

https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/94/9/16-020916/en/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2746509/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2869076/

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/raq.12344

Photo by https://unsplash.com/photos/nss2eRzQwgw